The spirit of the Sahara

Picture this scene: you are standing atop a sand dune in the Sahara, in a 360-degree panorama of utter vastness and silence. You face west, watching the sunset, the sky a blaze of orange, blue and red. You turn to face east: just as the sun sets, the full moon rises above the rim of the desert, milky white against the darkening blue sky.

Two hours later a group of travellers sit atop the same dune, wrapped in the traditional camel-hair burnous cloak against the chill of the night. The moon is huge and bright in this clear air, but even so the sky is also filled with stars. The travellers are sharing songs and stories around a brushwood fire. Nearby, camels sit impassively, silhouetted against the night sky.

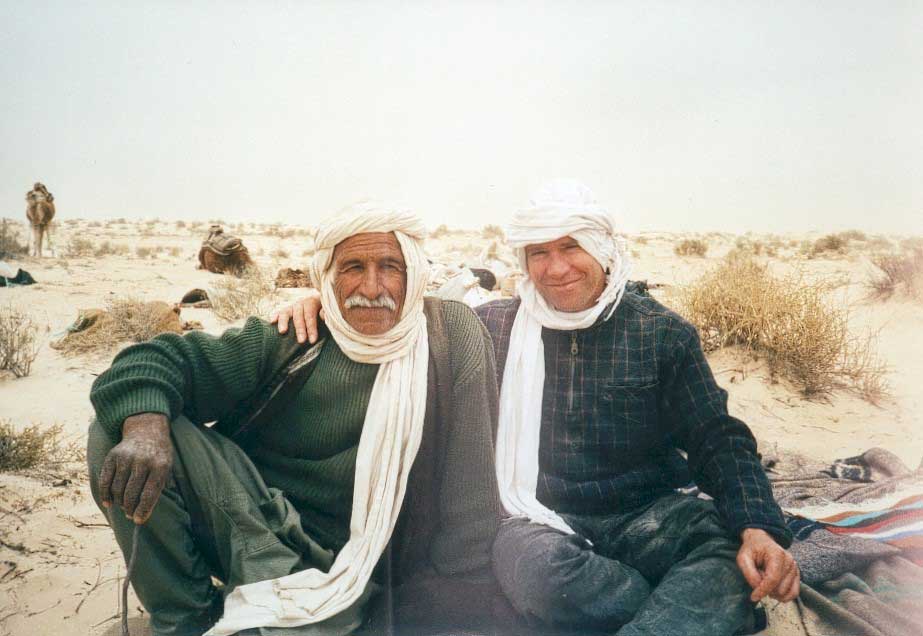

You could find such scenes in the Sahara for thousands of years: they are also a feature of the spiritual journeys I led to the Sahara for ten years. I have deeply loved this land and its people since my first visit in 1967: but my link with the desert has been transformed by meeting in 2000 a group of semi-nomadic Bedouin who have guided many retreat groups.

My vision for the Life in the Desert group which I led with Amida Harvey in 2001 was a spiritual journey with several elements: the experience of the desert; living and travelling with the Bedouin; practices like meditation, chants and prayers from the ‘desert wisdom’ spiritual traditions, Christian, Sufi and Islamic; and a vision quest, involving solo time in the desert. The group was intended to serve a range of interests and succeeded.

Part of my satisfaction in leading the group was knowing that our payment was an important part of the Bedouin’s annual income, since their traditional economy has largely disappeared due to climate change and other factors. Travelling through the desert by foot and by camel rates pretty highly as eco-tourism! The success of the 2001 group gave me the intention to lead one group a year to the Sahara, travelling with the same Bedouin guides, who became close friends for me. My last group was in 2010.

The Bedouin are profound teachers by their approach to life. Although their life is materially tough and basic, they are happy, dignified people. As they sit in a circle in the chilly light before sunrise, they are chatting, lighting the fire, making the bread, tending the camels and singing. I join them and ask myself, “Is this work time or social time?”, knowing that this is a western mindset and the question would be meaningless to them. Their songs move seamlessly from praise of Allah through romantic ballads to children’s play songs. Their days really are a flowing dance uniting, work, spirit, fellowship and recreation. Because of some of them speak good French, this is a rare chance to share the life and culture of people who are still within the semi-nomadic tradition.

The Sahara Desert is huge, bigger than Australia. It is largely untouched by the hand of man, and its power is inescapable. People describe this power in different ways, but almost everyone feels it. I would say that one feels the presence of Divine Unity, and the presence of nature in both its gentle soft, beautiful aspects and its raw, strong aspects, very directly.

One might say that the desert landscape is stripped of all but essentials, and it has the same effect on the visitor: one is brought back to basics and essentials very quickly. This also makes it an extraordinarily powerful place for spiritual practices, like using a wazifa (sound mantra) as a walking meditation while trekking barefoot across the sand, or devotional singing under a full moon.