written by Lynn Murphy

I’m curious about habits, about what I do and why I do what I do even when I don’t want to! And why the habits that I don’t want seem to be ‘stickier’ than the supportive habits I’d prefer to be running my unconscious life.

This interest has been tickled recently by reading Charles Duhigg’s book ‘The Power of Habit’. Habits are learned behaviours and patterns of behaviour that are repeated and reinforced in response to contextual cues. For example arriving home after a busy day may trigger you into automatically reaching for a glass of wine, your yoga mat or your running shoes. Experts suggest that at least 40% of the things we do every day happen without our conscious awareness (think arriving without remembering driving there…), because once we get familiar with a pattern, our brain automates it and stores it in the habit centre deep in the basal ganglia.

This interest has been tickled recently by reading Charles Duhigg’s book ‘The Power of Habit’. Habits are learned behaviours and patterns of behaviour that are repeated and reinforced in response to contextual cues. For example arriving home after a busy day may trigger you into automatically reaching for a glass of wine, your yoga mat or your running shoes. Experts suggest that at least 40% of the things we do every day happen without our conscious awareness (think arriving without remembering driving there…), because once we get familiar with a pattern, our brain automates it and stores it in the habit centre deep in the basal ganglia.

Conscious decision making requires more processing power and happens in a different part of our brains, hence the apparent disconnect between what we sometimes do, and what we’d like to be doing. Automated habits enable our brains to run more efficiently – we have more brain power available for tasks that really need it and efficiency means smaller brains. On a practical level smaller heads help our species to survive because they give us a more assured entry into the world and fewer women die in childbirth.

The Power of Habit

Denis Waitley

You may know me.

I’m your constant companion.

I’m your greatest helper; I’m your heaviest burden.

I will push you onward or drag you down to failure.

I am at your command.

Half the tasks you do might as well be turned over to me. I’m able to do them quickly, and I’m able to do them the same every time, if that’s what you want.

I’m easily managed; all you’ve got to do is be firm with me.

Show me exactly how you want it done; after a few lessons I’ll do it automatically.

I am the servant of all great men and women; of course,

I’m the servant of all the failures as well.

I’ve made all the winners who have ever lived.

And, I’ve made all the losers too.

But I work with all the precision of a marvellous computer

with the intelligence of a human being.

You may run me for profit, or you may run me to ruin;

it makes no difference to me.

Take me. Be easy with me, and I will destroy you.

Be firm with me, and I’ll put the world at your feet.

Who am I?

I am Habit!

Habits originate in different ways – some are taught in childhood (cleaning our teeth in the morning), some are learned in childhood (to feel anxious before visiting the dentist), some are prescribed in law (wearing a seat belt in a car), some we actively choose because experts tell us they are good for us (drinking more water and eating at least 5 portions of fruit and vegetables a day), and some make us feel secure (checking the door is locked before going to bed). But there many other habits that seem to arrive of their own volition and on which we can spend much conscious effort trying to change, either because we want to or because we think we should. Often though this is without success as we testify at this time of year when the optimism of January 1st commitments are forgotten, leaving only the legacy of a stronger belief that habits are hard if not impossible to change.

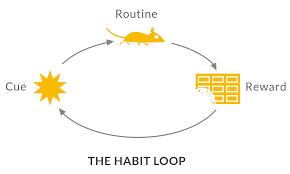

Much of the time we’re unaware of the patterns that run in the background of our conscious lives. There’s the old adage that ‘we make our habits and then our habits make us’, and it’s true, old habits are often comfortable, even if they’re not what we now want. Research outlined in the book dissects the structure of habits and in so

Much of the time we’re unaware of the patterns that run in the background of our conscious lives. There’s the old adage that ‘we make our habits and then our habits make us’, and it’s true, old habits are often comfortable, even if they’re not what we now want. Research outlined in the book dissects the structure of habits and in so

doing offers us a way of making new wanted habits to override the outgrown ones that we want to change.

Habits consist of a cue, a behaviour and reward. It’s the payoff that keeps the habit loop turning to the point where the cue and the anticipation of the reward trigger the automatic and unconscious behaviour.

Think of the classic coming home tired, pouring a glass of wine and slumping into the armchair. The real payoff is switching off from the working day and resting in the chair, but because we are socialised into believing that we deserve a drink at the end of a hard day we think that the wine is the reward rather than just the means of achieving the reward. Understanding this gives us choice about what we do – the same cue of coming home tired could cue some mindful breathing, having a shower or taking a quick walk all of which could give us the same reward of switching off and relaxing.

Overwriting with a new and preferred habit in this way is a long way from the willpower method of ‘I must drink less’ and is much more likely to be successful, particularly when it’s accompanied by a belief that the change is possible. The first step is to observe ourselves to become aware of our cues and payoffs and then to be curious and experimental in finding new and preferred ways of getting the reward.

Not all habits are made equal. Keystone Habits are ones that spill over to setting off a chain reaction of shifts in other habits, for example people who exercise regularly also display seemingly unrelated patterns of eating healthily, being productive with their time, sleeping well, using credit cards less frequently and showing more patience with colleagues.

Optimism (and pessimism) is a habit and can be developed. People with an habitually optimistic outlook are happier, have better health and live longer than pessimists; they also have more fun and are more enjoyable and affirming to share time with.

Until Spring really shows its warmth, the habit of being bright and sunny can take a little more focus and effort, so to get you going here are 3 ways of generating and enjoying some internal sunshine.

1. Regularly tune in to noticing all the positive things happening around you – the birds singing, a snowdrop in flower, the smell of a cold morning, the smile from a stranger, a hug from a friend. They don’t have to be big or extraordinary things to bring a sense of joy, you just have to notice and focus on them for a few seconds to absorb the pleasure.

1. Regularly tune in to noticing all the positive things happening around you – the birds singing, a snowdrop in flower, the smell of a cold morning, the smile from a stranger, a hug from a friend. They don’t have to be big or extraordinary things to bring a sense of joy, you just have to notice and focus on them for a few seconds to absorb the pleasure.

2. Spend some time everyday outdoors – most people find that walking in nature brings a sense of perspective and connection that help us relax. Focus on where you are and what you can experience through your senses to ensure that your mind comes on the walk as well rather than leave it working on a problem indoors…

3. Put your time and attention into what you can and do achieve rather than what you don’t. Better to set a few small goals and achieve them, than have a long impossible list and the almost inevitable focus on the things you haven’t done